Kiska, a lone orca at Marineland. Canada, 2011.

Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals

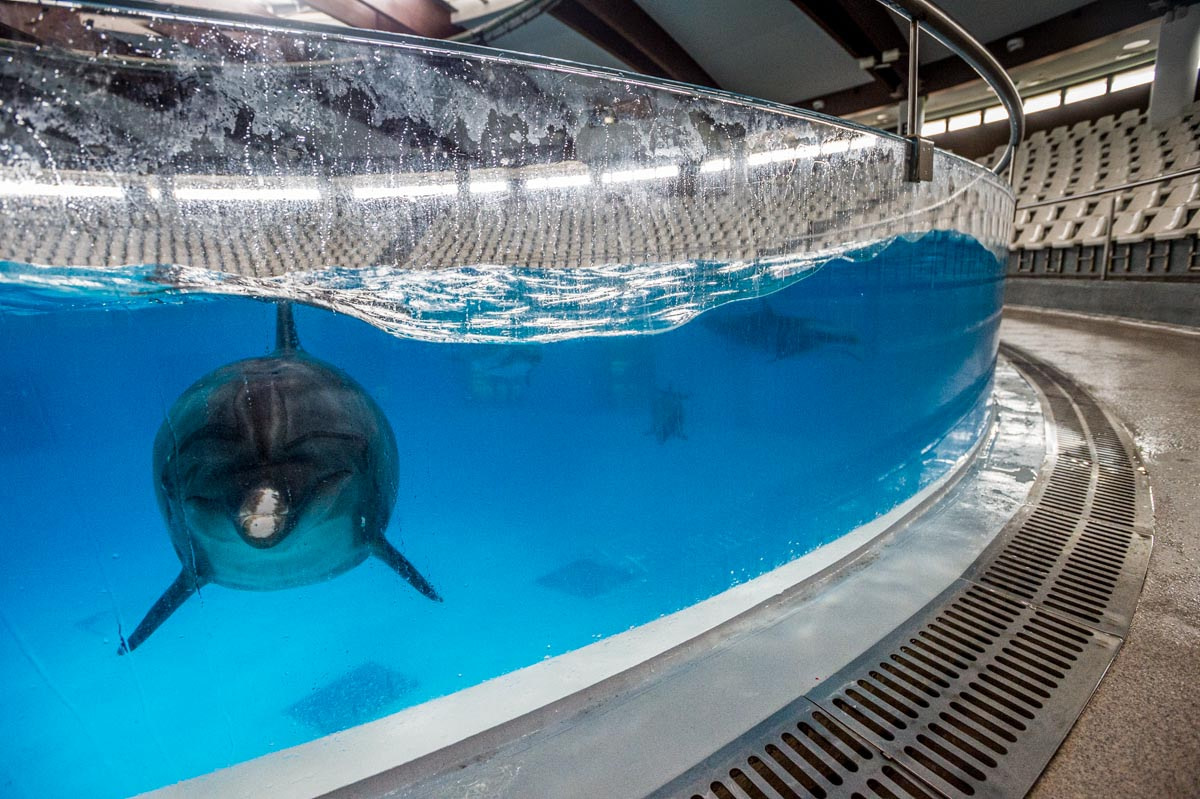

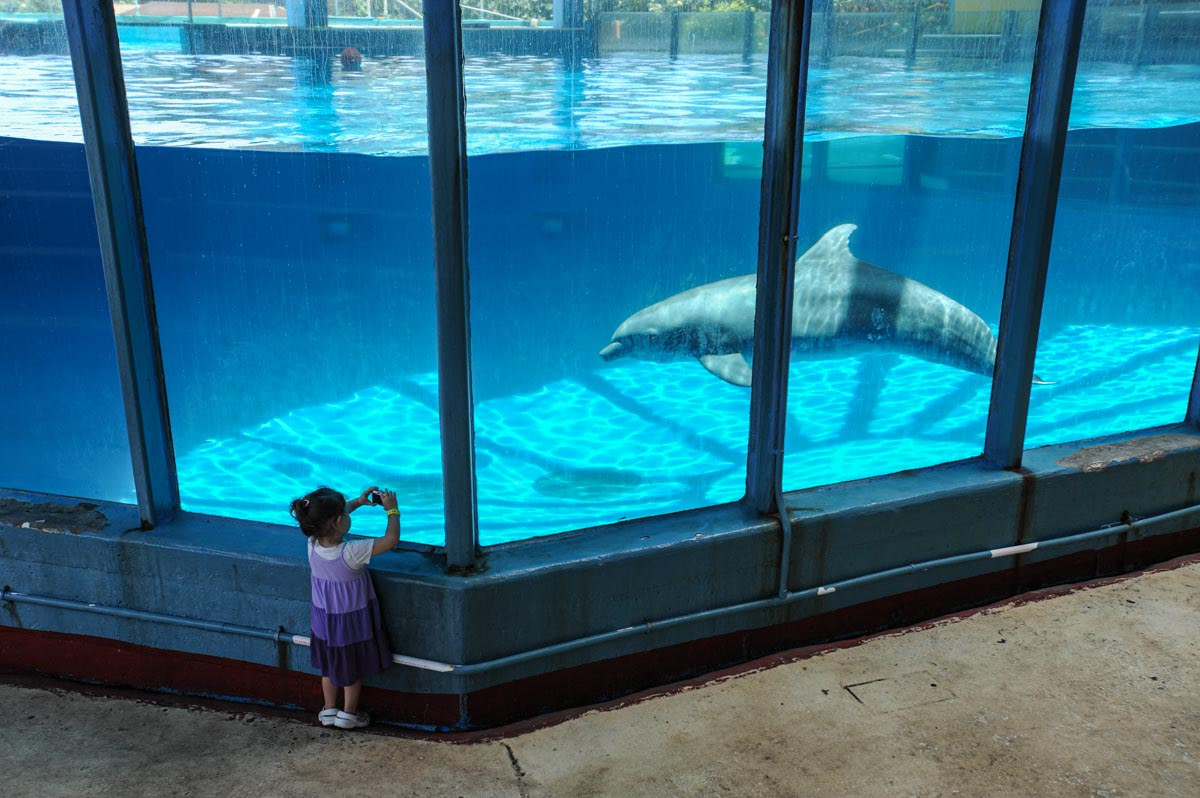

For the estimated 2,000 to 3,000 whales and dolphins currently held in captivity around the world, life is bleak, boring and unnaturally short.

These highly intelligent and social beings are bred, trained, sold and shipped like commodities, and suffer from physical and psychological ailments. An estimated 5,000 cetaceans have already died in captivity since the 1950’s, when the practice of keeping them in small tanks came to be, and all for the simple sake of entertaining humans (though sometimes under the guise of conservation and education).

Photographer: Jo-Anne McArthur

Thankfully though, this issue has gained much social and legal attention over the last several years, with great help from the now-famous 2013 documentary, Blackfish. Cultural shifts are occurring and legal changes are being made – though in some places more than others.

But even as these evolutions are taking place, and whale and dolphin captivity is slowly being outlawed in more places, there still remains the question of what should happen to those still living in captivity, unable to be freed.

At the Canadian Animal Law Conference (CALC) held in Halifax last month, experts on a panel entitled No More Whale Jails: Ending Cetacean Captivity in Canada, detailed the incredible story of how whale and dolphin breeding and captivity came to be banned in Canada earlier this year. From the senator who sponsored it, the lawyers who fought for it, the scientist, indigenous leader and grass roots activists who bolstered it, and the journalist who covered it, attendees heard just how – after the longest legislative battle in Canadian history – the unprecedented “Free Willy” bill was finally passed. The discussion offered great hope to those working to do the same in other parts of the world, where the business of keeping – and breeding – whales and dolphins in captivity continues to thrive.

In the U.S., for example, there are no federal laws banning whale and/or dolphin captivity, though a few jurisdictions have outlawed it. Keeping cetaceans in captivity has been banned in the state of South Carolina since the eighties, and in Maui, Hawaii since 2002. As of 2017, no orcas can be bred, imported/exported or used for entertainment in the state of California. However, there are still approximately 20 whales and more than 500 dolphins suffering in captivity across the U.S. today.

It is important to remember, however, that the existence of a captivity ban does not mean that cetacean suffering has ended. To the contrary, places where bans have been enacted continue to house suffering and exploited cetaceans.

In Canada, at least 62 cetaceans are still languishing in captivity, including a single orca, 40-year-old Kiska, and several young belugas who could potentially remain in their tiny tanks for decades.

It would appear that cultural and legal tides are slowly turning regarding whale and dolphin captivity and exploitation. This is not the case for many countries in Asia, however. In China, for example, the number of whale and dolphin display facilities has grown rapidly in recent years. New marine parks are reportedly opening almost monthly in China, with the number of facilities nearly tripling since 2015. In order to keep up with the demand for these animals, an orca breeding facility was opened in China in 2017, as a way to both supplement the number of existing wild-caught animals and to replace those who die unnaturally young in captivity.

It is important to remember, however, that the existence of a captivity ban does not mean that cetacean suffering has ended. To the contrary, places where bans have been enacted continue to house suffering and exploited cetaceans.

In Canada, at least 62 cetaceans are still languishing in captivity, including a single orca, 40-year-old Kiska, and several young belugas who could potentially remain in their tiny tanks for decades.

So far, this has not happened.

Photographer: Jo-Anne McArthur

To view more images from this story, please visit our Aquarium gallery on the We Animals Stock Site.